The Cognitive Neuroscience of Placebo Effects: Concepts, Predictions, and Physiology – Geuter et al. 2107

Introduction:

This paper looks at the effectiveness of sham treatments/placebos and the manner in which they affect the physiological mechanisms related to the benefits they cause. A cool way they phrase this is by saying “How does the central nervous system convert an inert sugar pill into physiological changes in the brain and body?”. The benefits of placebos can be seen in a variety of conditions like pain, parkinsons disease, nausea, depression, immune responses and cognitive performance. Reminds me of the time Harry gives Ron a “sip” of his felix lucky potion and Ron proceeds to play extremely well in quidditch while in reality Harry never gave him any at all.

Psychological theories of Placebo effects :

Important processes that affect placebo success are the expectations of the patients, their learning history, instructions from the caregiver and social context. The effects of placebo are also viewed as classical conditioning. The effects of placebo are based on the pairing of treatment cues for example when using a needle for injections combined with a real drug, followed by providing the needle injection with a saline solution has provided benefits just through the cue of administering a drug (Analgesic is a term used repeatedly through the study and it means a drug is relieving pain).

There is also numerous evidence cited in the paper that outlines how crucial the thought process of the treatment model is as well as the resultant expectations from the model in placebo effectiveness. Some of these studies have shown that verbal cues are enough to create a sense of relief to subjects when dosed with a placebo. This boils down to plausibility of the placebo to provide relief which is based on previous knowledge integrated with information taken from the situation into a mental framework of how the treatment is supposed to work. For example patients that use creams for local pain relief, and use it specifically on the right hand create a mental framework that their right hand should hurt less than their left. Thus when the placebo is administered in a similar manner, the subject recalls the former experiences and creates expectations of the current situation. Obviously if you do this for long periods of time the effects of the placebo could dwindle, thus the effects of placebos can be stable as long as the meaning and confidence of the placebo remains stable within the patient. The issue with this is that cognitive processes in people are extremely flexible, so the placebo’s effectiveness can change dramatically if even a small cue is changed if it has a larger meaning to the patient. For example changing the brand name or economic value of a certain medicine can have greatly impact the effectiveness of placebos. A theory as to why placebos occur in the first place is that a subject’s ability to form predictions reduces the uncertainty about which actions would be most adaptive.

Placebo effects and multidimensional priors:

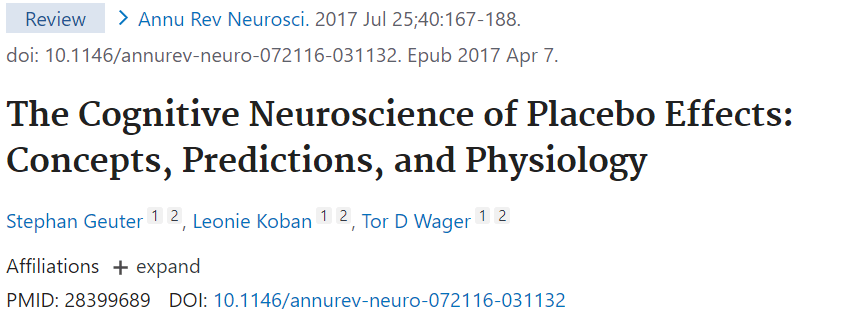

In more specific neuroscience terms, a theory for why placebos exist is because the nervous system, from the spinal cord and retina to the cortex are adapted to infer/predict things about behaviours that would be optimal given the environment/situation they are in. Part of this adaption is using the cues around them and prior knowledge gained in the environment to constrain their perception, almost like putting blinders on a horse, and this primes them for the situation. This has potential advantages in speed and accuracy when in noisy sensory environments that may overwhelm the subject. We see this in retinal ganglion cells that not only respond to stimuli but can anticipate and predict the position of a moving stimulus. Modifying your sensory input to prioritize the needs of the situation to focus more on important things also plays a factor as to why placebo effects exist. For example when running away from a predator that has attacked a subject, suppressing pain for locomotion is advantageous.

Context is important to perception of a situation, for example runners who wear weights believe the track to be longer than normal, this is similarly seen in perception of colour when people believe an object to be more yellow when it resembles the shape of banana. Once again this is to lessen the noise from the environment to improve judgement. However, on the downside, too much of this can result in seeing things that are not there and inducing hallucinations.

A method in which to prolong the effectiveness of placebos is through partial reinforcement, this means providing the real drug in lieu of saline for a proportion of the experimental trial. This reinforces the expectations without having to provide a huge volume of the drug consistently. The subject becomes unsure of when the benefits are a result of the reinforcement or the placebo. The reason all of this is multimodal is because the subject needs to understand whether an outcome will be negative/positive, what will actually occur, and what reactions should be given both emotionally and viscerally. Thus placebos work best when utilizing multiple sensory pathways to reinforce the idea of the treatment, and when they harmonize together they can shape autonomic, neuroendocrine and affective responses in specific ways. The ventromedial prefrontal cortex is very well suited to integrate multiple forms of information thus plays a large role in placebo effectiveness.

Brain Circuits for Descending Control:

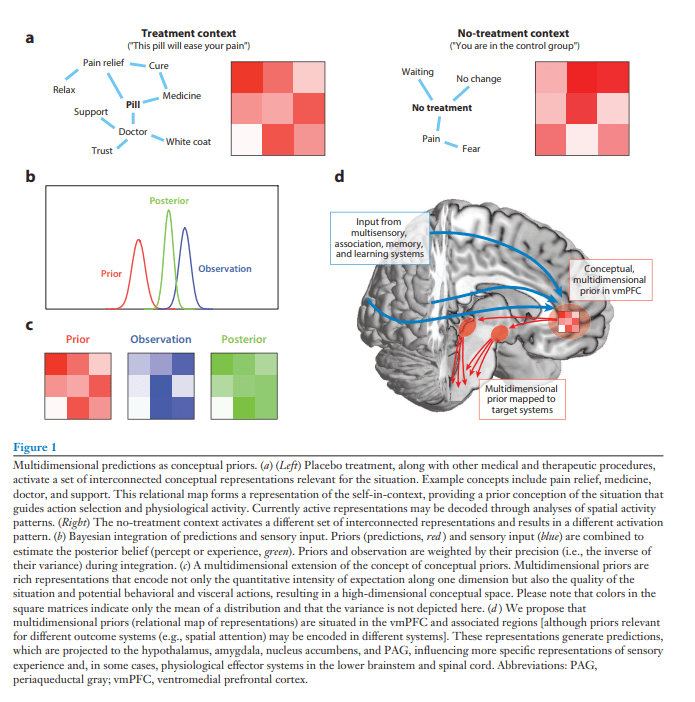

Multiple pathways attribute to the effect of placebos, for example some placebo analgesia coming from verbal suggestions are blocked by opioid antagonists. While in other instances when analgesia results from conditioning with non-opioid drugs, then analgesia seems to be opioid independent, but could still be blocked by cannabinoid antagonists. Some of the components involved with placebo analgesia uses the cortical-brainstem system, including the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC), ventromedoial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC), lateral orbitofrontal cortex (lOFC), nucleus accumbens (NAC), periaqueductal gray (PAG), and rostroventral medulla (RVM).

The current working model is that a system for mental assessments is involved in understanding the context surrounding treatment and generating predictions that become used for placebos. This system is centered around the regions mentioned earlier, and these regions are capable of generating emotion. This system also connects with associative learning structures and effector systems that can then affect perception, emotion and physiological responses. There are 2 major types of effector systems 1. Direct neuronal control, like placebo analgesia ; 2. Indirect control via endocrine glands releasing hormones into the blood stream, like conditioned immunosuppression. These pathways can then extend to cortical regulation of hormone release and other transmitters as well. In one study, the mere suggestion of hyperalgesia (this means that severe pain is experience when a moderate amount of pain is expected) caused increased plasma cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels.

Descending Modulation of Pain:

The afferent nociceptive pathways, aka the pathways dealing with pain, originate from nociceptive neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord and work with a descending modulatory system that can both increase and decrease the sensation of pain. Key parts of this system start in the cingulate cortex and ventromedial prefrontal cortex and projecting directly and indirectly into the periaqueductal gray. The periaqueductal gray receives more input from the subcortical regions, amygdala, nucleus accumbens, and hypothalmus, all which have bidirectional connections to the vetromedial prefrontal cortex. Afterwards, the periaqueductal gray sends projections to the rostroventral medulla and locus coeruleus (LC), which in turn synapse onto neurons located in the spinal cord dorsal horn. There are 2 types of cells known as ON and OFF cells in the rostroventral medulla that can either initiate the feeling of pain or stop it. They found that these areas were involved with placebos through neuroimaging studies, for example positron emission tomography studies used tracer binding specifically to mew opioid receptors and extended findings of placeo research by demonstrating that opioidergic neurotransmission in the ventromedial frontal cortex, lateral orbitofrontal cortex, amygdala, nucleus accumbens and periaqueductal gray were increased under placebo. Increased coupling was noticed between the ventromedial frontal cortex and periaqueductal gray under placebo analgesia, as well as placebos referring to a pleasant touch experience induced by verbal pleasant suggesstions. This seems to indicate that pain and pleasure pathways overlap in neural regulation. The ventromedial frontal cortex is also key to placebos relating to anxiety and reward learning in parkinsons disease.

Descending modulation of autonomic and cardiovascular function:

This section deals with outlining the descending pathways that regulates the autonomic nervous system (ANS) which is composed of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and parasympathetic nervous system (PNS). SNS is known for signaling the adrenal medulla that releases adrenaline into the blood system and increases blood pressure as well as affects the immune system. Sympathetic efferents originate from the intermediolateral column (IML) of the spinal cord while the parasympathetic efferents leave the CNS via cranial nerves. The vagus nerve is the most important nerve in the PNS since it carries both afferent and efferent projections. Both the SNS and PNS receive input from the same set of brainstem nuceli including the rostral venotrolateral medulla (RVLM) and a few other parts. These in turn control the influences onto the periaqueductal gray, amygdala and hypothalamus that are key regions in placebo effectiveness. Directly stimulating the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray in rats has been known to decrease blood pressure, heart rate and skeletal muscle tone while stimulating the lateral portion does the opposite. This is also seen in humans.

Cortical regions involved in ANS control are the ones mentioned previously to work with placebos like ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the cingulate gyrus. A recent study has also shown that there is a multisynpatic pathway connecting the ventromedial prefrontal cortex to several motor and premotor areas and to the adrenal medulla. This study showed that the components we observed involved with placebo effectiveness is directly linked to a major endocrine gland that can cause the differences we observe.

Examples of the effects expectations and thoughts can have on the autonomic responses has been seen in multiple studies. For example the expectation of giving a speech and increase sympathetic activity like a nocebo effect. Another example is patients with hypertension when injected with saline in the proper context showed long lasting reduction in blood pressure. Successful placebo analgesia can also lead to reduced skin conductance responses and pupil response to pain.

Descending modulation of immune responses:

There are 3 main pathways in which placebo treatment can affect immune function: 1. neuroendocrine control like the hypothalamic pituitary adrenal axis (HPA axis), 2. the sympathetic-medullary-adrenal axis (SMA axis), 3. direct autonomic-to-immune communication. The HPA axis activation results in cortisol to be released from the adrenal gland which inhibits proinflammatory cytokines. SMA axis activation has been found to originate in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex which is a big part of placebo, and this axis controls release over cortisol, epinephrine, norepinephrine and cytokines. These pathways provide a functional neuroanatomical route for placebos to affect immune function. In people, the effects of placebo on immune function have been studied with effects such as immunosuppression, psoriasis, asthma and the modulation of inflammatory cytokine release by emotion induction. An example of this was found with rats that used an immunosuppressant known as cyclosporine A, which was paired with a flavoured drink, when the subjects were only given the flavoured drink, researchers saw a reduced IL-2 production in the blood samples which mimicked the effects of cyclosporine A. This response extinguishes over time, but can be extended by using random doses of the real drug to reinforce the placebo.

Comparison of descending modulatory pathways:

Basically everything above outlines how placebos can affect multiple organ systems through a multitude of pathways, particularly through the ANS. The brain regions jointly involved in placebo effects of pain, immune function and autonomic processes include the periaqueductal gray, amygdala, hypothalamus and insula. It makes sense that the amygdala would play a critical role in placebos since this part of the brain is used heavily during associative learning, which is crucial to placebos. The connections of the amygdala to the hypothalamus and periaqueductal gray allow for the placebo to create effects in the endocrine, autonomic and nociceptive systems. Specifically in fear conditioning the hypothalamus is responsible for mediating the conditioned artieral pressure response while periaqueductal gray is tasked with behavioural freezing responses. Both of these could play a role in eliciting the desired effects of placebo treatment. Also the manner in which these components are activated, affect the result seen, for example when we discussed what occurs when you stimulate different parts of periaqueductal gray we found that they created opposing effects.

The importance of the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) should also be highlighted as all the regions in placebo treatment receive direct input from the vmPFC. Even though vmPFC is assumed to play a role in immune function related placebo, it hasn’t been tested. However there is an example of subjects displaying higher rates of success with a anti-histaminic drug after watching a commercial about it, hence prepping them for the drug given.

Conceptual representations in prefrontal cortex:

The effects of placebos and the systems they interact with have also been tested by altering the brain chemistry/structures to see how it affects effectiveness of placebos. For example Alzheimers and transcranial magnetic stimulation both disrupt the prefrontal function and in turn reducing placebo success rate. The vmPFC is critical to placebo effectiveness because it is in charge of visceromotor action, homeostatic processes, emotional evaluation and decision making. It also allows the integration of information leading to emotional meaning, outcome expectations, emotion regulation, value representation, formation of new concepts, representation of current states, conceptualizing future states of the self.